Increase your multisport kayak speed and safety

- steve3144

- Dec 22, 2020

- 19 min read

Updated: Mar 13, 2023

Steve Gurney shares technique tips on using your rudder and hull design for more race speed, while also improving your safety on the river.

It’s not what you do with your paddle.

It’s not how fit and strong you are.

It’s not whether you can roll either.

THE most important and fundamental skill for kayaking is to use the kayak hull as your tool.

The hull has different angles, curves and edges in its design, designed to interact with the various elements of the moving water surrounding your kayak.

A good paddler will “be at one” with their kayak or feel like the kayak is an extension of their body positioning the hull exactly where they want it to be, carving, slicing, lifting and railing.

A beginner multisporter in a river likely feels none of this warm, kindly, connection.

Understandably they’ll feel unfamiliar and disconnected, that their boat is a terrifying, unpredictable beast ready to toss them out to the taniwha, whirlpools, and bluffs.

Summary:

In this article, I’ll explain the how, why and when to use the hull shape to aid turning, positioning, safety and overall speed.

Beginners often assume that fitness, grunt and muscle power are the basis of a river kayaker’s prowess. But I stress that this is not the case, the basis of good river paddling is the art of kayaking, the skill rather than the grunt, how to use the hull efficiently. It may seem subtle, but this skill is what will give consistently fast river speed, it will make river paddling fun and satisfying, and is the difference between a beginner and a confident paddler.

these skills will help a kayaker harness the best speed from the river water that is already moving in their direction. Ie positioning their kayak in the fastest water.

having these skills enables the paddler to put 100% of their effort into going forward instead of nervously hesitating and support stroking.

having the foundation of good skills, is then a good platform to build fitness and grunt.

Rail-steering

Many multisport kayakers don’t even realise that there are several ways to steer your kayak with more efficiency than a rudder. Rudders are actually terribly inefficient, (but are sometimes a necessary evil). The trick is to know:

how to use multiple steering methods

when to use each different method

There has always been a debate about when and how to introduce rail/bilge steering when someone is learning to kayak. I firmly believe that it is logical to teach rail steering right from the start. I opine that failure to teach all methods to steer the kayak teaches bad habits and confusion, which ultimately undermines safety.

To extract the best speed and safest function from a multisport kayak a beginner needs to be instructed comprehensively in ALL methods of steering, when, and in what order to use the various methods to turn the kayak.

There are times when it’s better to steer by rail-steering and there are times when rudder steering is best. I’ll explain the difference in clear detail below.

Lifting the edge

This article also explains how to use the edges (or the rail). Perhaps the most dramatic and eye-catching example is in slalom where a competitor stands their kayak on its tail to catch the deeper current and turn it quickly through the gates. They do this by slicing the tail of their kayak under the water using the sharp “rail” edge of their stern.

Multisport kayakers, on the other hand, need to do the exact opposite, instead keeping the sharp edge of their rail above the current to prevent the rail catching side currents.

Knowing how to use the edge is:

Life-saving if you’re caught on a strainer hazard.

As a beginner it’s the difference between staying upright and capsizing. “Fart at the fast-water”

Contents

What is the rail?

“farting at the fast water”

Which is the fast water? It’s confusing at first!

Which is the fast water?

How to get extra speed from your kayak.

Priority order of strategies of planning and turning methods

How to make turning easier for yourself

They’re easy when you know how to use your rail

They’re actually easy, here’s the fast line

How to navigate safely

Tricks and tips for more speed with rail-steering

A diagrammatic representation and some tips

The NZ phenomenon

Kayaking 101 railing basics.

This is how I teach beginners.

As you’ll see in [Figure #1], all kayaks have a rail (an edge) that’s relatively sharper than the hull. It’s where the deck and hull join together.

Tributary or braid flow joins from the side

“Fart at the fast water!” … by lifting the rail.

…The most important and fundamental technique for moving water (and surfing a wave).

You’ll recall being taught this, or some variation of this as a beginner.

The fast water that we refer to here is fast relative to the speed and direction of your kayak, (not relative to the land. Imagine that you’re a starfish stuck on the hull of your kayak and can only see or feel the water 10 cms around you).

By lifting the rail or edge of the kayak when fast side-water comes from the side (instead of from the usual straight-ahead direction), the kayaker prevents the fast water catching the edge and capsizing the kayak. Instead the fast water from the side slides under the hull allowing the kayak to kind of “skim” sideways over the fast water in the same way that a surfboard would. [Figure #1]

In a river situation this “fart at the fast water” rule is applicable for:

[Figure #2] when a significant tributary or braid joins the flow that the kayaker is paddling in

[Figure # 3] cutting out into the main river flow from an eddy or a put-in

[Figure # 4] cutting into an eddy for a break, portage, inspection etc

[Figure # 5] Surfing sideways on a wave (e.g. at the beach, or a large breaking wave in the ocean or lake, or a standing wave in a river, or stationary on a buffer wave such as a bluff) you’ll be farting at the fast water relative to the kayak hull.

[Figure #6] Being caught on an obstacle such as a tree or singular rock.

Cutting out of an eddy into the main flow

Cutting out of the main flow into an eddy

Surfing sideways on a wave

Scenario d) is fun! Surfing sideways!

This is most common when surfing waves at the beach, but exactly the same principle applies for being sideways in static waves in a river or sideways to breaking waves on lakes and the ocean.

In [Figure # 5] the fast water relative to the kayak (if you were a starfish stuck to the hull of the kayak looking at the water right there), is the smooth green/blue water coming from the side because the kayak is actually surfing sideways down the wave. So we need to activate our core strongly and consistently and lift that buttock and fart at the relative fast water!

Caught sideways on an obstacle or strainer

Scenario e); caught sideways on an obstacle or strainer:

It is critically important that you keep that rail lifted as in [Figure #5 and #6 top] and to do this consistently, paddlers need to have a strong core (rail steering develops this). Failure to keep the rail up will could mean drowning/death. If the rail drops to the water line, even for a nano-second, the current will catch it, flip the kayak down under the water, wrap it around the obstacle, fill the kayak with water, and trap the kayaker underwater to drown. The power of the river is immense, no matter how seemingly slow the flow, and there is no way that a single human will win against it. Please have a healthy respect and avoid being caught in trees.

Firstly avoid trees, plan well ahead and if in doubt get out. Pull over well in advance and portage around the trees.

If (when) you do accidentally end up caught on a tree, a log, a solitary rock, it’s critically important to strongly lift the rail with your knee to fart at the incoming fast water, and most importantly, you need to consistently hold the rail up with strong core muscles. You’ll need to keep calm and make some quick decisions:

You may be able to hold the rail up and push your way around the obstacle you’re caught on, thus floating free.

If you judge this is impossible or dangerous then abandon your kayak, pull yourself up and out, climb the tree, climbing away from the incoming water.

If you have capable kayaking partners practiced in rescue, then there’s a small chance they’ll get to you before you’re too exhausted, but it’s unlikely they can help you in time.

Prevention is best. Plan ahead and keep your core strong in training sessions by practicing rail steering as described later in this article.

Rail-steering

Many multisport kayakers don’t even realise that there are several ways to steer your kayak with more efficiency than a rudder. Rudders are actually terribly inefficient, (but are sometimes a necessary evil).

The trick is to know:

how to use multiple steering methods

when to use each different method

Rail-steering (also known as bilge-steering) is tipping the kayak to one side by 20 to 40 degrees to alter the shape of the hull below the waterline such that it turns the kayak without the use of a rudder. The kayak turns because differential in the water pressure along the length of the hull. It is a very efficient way to steer and its inherent in the design of the hull. (yachts do this too) [see figure #7]

Rudders are a later addition to the multisport kayak phenomenon in NZ.

Rudders can be viewed as “lazy”, because when used naively and inefficiently they are “steering by blunt force”. But rudders do have their place! River and sea kayaks are designed with more rocker than a flat-water kayak to be more manoeuvrable, and thus are more easily “spun off line”, and thus, a rudder is quite useful in keeping a river kayak in a straight line, for helping in a side wind, and for making emergency fast turns.

Intermediate and advanced level kayak hulls are designed to turn very efficiently and quickly when leaned over.

Beginner-level kayaks don’t respond as easily to rail-steering, mainly because their extra width/buoyancy makes it harder to lift the rail, but they will still rail-steer.

Rudder advantages:

It’s easy and relatively simple. (Rail steering can be counter-intuitive and hard to learn at first)

Rudders are useful in side-winds

Rail-steering advantages:

Faster kayak speed. (rudders can be a “blunt-force” way of turning)

Inherent in the design of river boat hulls and enables quicker turns. (thereby safer)

Safety skill for when the rudder breaks. Negating the need to pull out of the race/trip.

Teaches core control and proprioception, therefore better athleticism.

Procedure for getting down a river as fast and as safely as possible:

What I’m describing below is in the context of getting down a river as quickly as possible in a race. Recreational paddling or playing in currents or waves (river and ocean) has a different focus/paradigm and you may use the steering methods in a different order, but the principles of turning are the same.

Rudder steering should be the last priority for steering in a race because just like doing a handbrake skid, it slows your kayak.

For a racing situation, here are the best steering methods in order of what I consider to be fastest priority.

1/ Scanning ahead and planning your route

This significantly reduces the need for turning. In other words, positioning your kayak in the current.

For maximum speed in a race, we (generally) want to position our kayak in the fastest water.

Fastest water will be where the bulk of the flow is. (Fast flowing water is generally characterised by long wave trains and a long wavelength between crests, and if the water is clear (not muddy, milky), the deep fast water is usually a deep blue colour.)

When our kayak is positioned in the bulk of the flow, there is actually very little need to turn it because the water is flowing exactly in the same direction that we want to paddle (ie we want to stay in the bulk flow)

You can also plan ahead to utilise various currents, eddy lines, boils, buffer waves or wind to turn your kayak. (eg the buffer waves off a bluff will straighten your kayak)

2/ Rail steering. (Bilge Steering)

Leaning (railing, tilting) the kayak over to one side using hips. Lift left hip to turn left; and lift right hip to turn right. [Figure # 7]

Bilge steering creates a long way and a short cut for water flow as it divides around each side of the hull. In other words, bilge steering creates a “foil”. This means that the flow around the long way will have a tendency to be less dense than the flow on the short cut. The hull moves sideways to equalise the pressure difference, thus turning.

Because a kayak hull is long and carefully designed for laminar flow, bilge steering is much more efficient when compared to rudder steering. Rudder steering adds friction to turn. [see Figure #7]

Skinny (tippy) kayaks bilge steer very easily.

Wider hulls are less responsive to bilge steering, but still turn with a bilge steer, and this will be helped heaps by simultaneously doing a sweep stroke as described by [Figure #8].

3/ Sweep strokes. [Figure # 8]

Incorporated into your normal paddling cadence.

Simply make your paddle stroke on one side longer, stronger and wider.

No need to double stroke, simply insert a sweep stroke instead of a normal stroke.

Anticipate the need to turn and insert a sweep stroke early on, thus making it much more effective and easier to do. Sweep strokes are most effective used early. Anticipate a turn and initiate or correct before the kayak gets its momentum into a turn.

Sweep strokes are much more efficient than a rudder and are best done in conjunction with bilge steering.

4/ Rudders

Rudders are inefficient and best used for:

fine tuning the turn at the last minute

to avoid a tree strainer

a last-minute emergency change to avoid a surprise

Combine these 4 methods

A fast paddler will usually combine some or all of these 4 methods above, starting with: #1 Planning ahead and progressively adding #2 Rail-turns, # 3 Sweep strokes, and finally #4 Rudder as needed to progressively produce a tighter and quicker turn.

The conflict when cutting into and out of an eddy:

Where there is a conflict between rail-steering and “farting at the fast water” is in [Figures 3 and 4] above. In these 2 cases, rail-steering would theoretically help make a quicker turn, but it risks catching the edge and capsizing.

“Farting at the fast water” is the safest and always trumps, or takes priority, because the water coming from the side will very strongly grab the rail or edge and capsize the kayak.

An expert kayaker can sometimes rail-steer for [Figures 3 and 4] but only when there is very little side current (eg a weak eddy). But the gains to be made are so negligible that it is always best to be conservative and fart at the fast water.

Be assertive!

Most beginners are too conservative and need to commit more to:

lifting their rail higher out of grasp of the water intersecting from the side. It’s very helpful and comforting to use a support stroke (low brace) on the opposite side.

Good forward speed when crossing an eddyline helps heaps with kayak stability, and the efficacy of the low brace support stroke. (like water-skis, they both need speed to be stable)

But safety always trumps rail steering.

If you have fast water coming from the side:

Fart at the fast water!

Summary so far:

As you become more confident as a multisport river racer:

you will learn to rail steer more and rudder steer less

you’ll learn to anticipate early when to use a sweep stroke to help a turn

you will be able to judge from closely observing the incoming fast water from one side or the other how aggressively you’ll need to fart at the fast water and whether a low brace support stroke is needed or not, or whether railing is enough and you can keep powering forward with full power.

You’ll develop strong core muscles and good proprioception by using your rail often.

Here are a some more hydrodynamic situations to consider:

Waves with wind

Boils

Bluff rapids

Dangerous strainers

A. Waves and wind

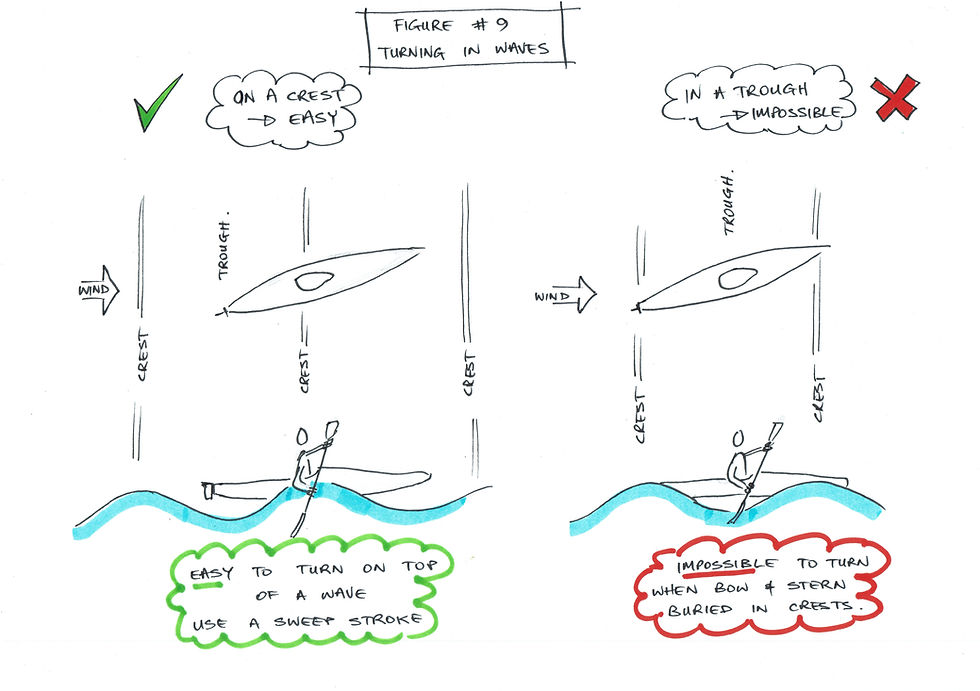

Kayaks will turn easily when they’re on the top of a wave. It’s like a “see-saw”. By picking the timing, use a strong, wide paddle stroke when the crest of the wave is under your cockpit, and then the kayak will spin super easily! [Figure # 9]

By contrast, it will be impossible to turn a kayak when you’re in a trough with the bow and the stern buried in a wave each. [Figure # 9]

You’ll find this wave turning technique useful when:

You’re on a lake or estuary running with the waves and wind; or when the waves and the wind are on your rear quarter. The kayak will invariably broach in the trough between 2 waves and try to round up into the wind. So, you’ll need to wait until you’re sitting on top of the crest to do a strong sweep stroke to pivot the boat back on course.

You’re in a rapid with a wave train but you need to move slightly to the side of the wave train. (obviously, scanning and planning ahead would prevent this in the first place) [Figure # 10] A wave-train is a series of static waves down the middle of a rapid. The wave-train is where the water is fastest, theoretically a good place to position your kayak, but it is often slower because the kayak is violently “see-sawing” and the waves crests crash into the kayaker’s chest. The best race-line is just beside the wave train 50cms to the side of the crests where the water is flatter, the flow is just about as fast, but the kayak won’t see-saw. To re-position your kayak out of the middle of the wave-train, wait until you’re on top of a crest and then do a sweep stoke to change the kayak direction. Take care to do just a moderate direction change, otherwise your bow will catch the eddy beside the wave-train, and you’ll spin sharply upstream. Once you’re 50 cms beside the wave-train, be ready to quickly rail-steer and sweep-stroke your kayak straight back in line with the current.

Wave trains

B. Boils – using your rail [Figure #11]

Boils occur in deep, fast rivers. They can be a little intimidating to beginners, but once you figure out the dynamics, they’re actually fun! When racing it’s best not to avoid them, just cut through them.

As a summary, the boil will shunt the bow sideways, which is totally fine so long as you plan ahead and anticipate logically that it will do this, but the boil will very soon automatically correct this change of direction so long as you relax, rail, don’t move your rudder, and keep your speed up. [Figure # 11].

As your kayak bow intersects a boil, keep your speed up, simply lift the rail to “fart at the fast water”, keep paddling, or do a low brace support stroke if you’re not as stable as you’d like to feel.

The trick is; once you’ve cut into the boil, keep watching the water ahead to anticipate which side the next “relative fast water” will come from. You’ll need to swap and lift the other rail, because the boil will have shunted your bow sideways and as your bow exits the boil back into the body of the river, the new water is the body of the river effectively coming in from the opposite side to the boil to straighten it up!

The nett effect of passing through a boil is that the boil has simply shifted the boat sideways, but you’ll still be in the fastest part of the river. It’s fastest to NOT use your rudder and it’s actually unnecessary, simply rail the kayak as described above to prevent the boil catching your rail and go with allowing the boil to temporarily turn you and then back again.

Rail-steering as described, actually helps turn the kayak in a useful direction, to counter what the boil does.

Initially a beginner will be comforted by using a support stroke (on the opposite side to the incoming fast water) to help the “farting” action, but with practice you’ll learn that you can safely apply full paddle power whilst railing, using the power stroke for support, and that this full speed ahead will aid stability. As you get better at it, you’ll feel a smooth carving motion with your hips as you change from one rail to the other, your kayak describing a rolling, mild “S” move.

C. Bluff rapids

Most paddlers fear bluff rapids, but once you understand which rail to lift and when, you won’t need to change your pants! They will become tactically fun, and will be your secret weapon to gaining heaps of time and race places over less confident paddlers.

[Figure # 12]

The keys to mastering bluff rapids are:

Planning well ahead

Positioning your kayak wide to start with so it’s not a tight turn

Knowing when to drift sideways a little

Understanding which rail to lift if you meet the buffer wave intersection with the fast water

Avoiding the eddy at the bottom.

Plan well ahead, looking for the fastest, deepest water. If you position yourself in the fastest water there’s less work to do in steering and railing, it’s actually much easier than any chicken route (and chicken routes usually have “sniper-rocks” that will damage your boat)

Start wide of the centre line so you don’t need to do any tight turns. [see figure # 12]

Position your kayak a little bit sideways so you’re drifting sideways toward the bluff and buffer wave… at any point you can put the power on, and totally miss the buffer wave.

Lift the rail facing the incoming fast water (the upstream rail in this case) as you continue paddling.

Adjust your speed so that you power straight through the “sweet spot”.

If by chance you drift sideways into the buffer wave, it’s totally fine so long as you keep lifting your rail, “farting at the fast water” coming at you from the rapid above. The buffer wave below you is benign, having lost its force and energy when it met the bluff rocks. The buffer wave can look intimidating, but it’s actually helpful in keeping you away from the bluff rocks like a pillow. The fast water coming at the side of your kayak from the rapid above you has the power to catch your rail, unless you lift it high.

The ideal line is to avoid the buffer wave totally, positioning your kayak halfway between the buffer wave and the eddy on the opposite side at the bottom of the rapid. It’s sometimes called the “sweet spot” because you’ll feel a sweet burst of acceleration here! [Figure #12]

Caveat, caution, good to know:

Very rarely (1%) the bluff might be undercut, and you’ll be able to predict/see this as you plan your approach, by the absence of a buffer wave. An undercut is very dangerous because you could get forced under water, but it’s very easy to see and avoid it if you position your kayak on an angle, [Figure # 12] which enables you to power away from danger.

It’s exactly the same dynamics and kayakers’ route for tree strainers or solitary rocks that can occasionally be found along a bluff face.

D. Tree strainer danger! [Figure # 13]

Scanning and planning ahead is never more important than for dangers such as trees.

If in doubt, get out. If you can’t see around the strainer or are unsure about your ability, get out well above it so you can inspect or portage.

If it’s safe to paddle:

safety is much more important than speed, so this is one case to use your rudder as much as needed, but if you plan ahead you should only need to use your rudder a little, (and besides it’s good to know you have a buffer of “rudder safety” up your sleeve)

Plan your route well ahead, and conservatively, keeping as far away from the tree as you can in case the current is stronger than you thought.

Ease up a little on your effort so you have some acceleration available if needed to get out of trouble.

Angle your kayak in the direction of escape [see Figure #13] so that you’re drifting slightly sideways, but ready to accelerate away if needed. You can safely use a bilge steer to turn more away from the trees because this is also “farting at the fast water”

Training ideas for perfecting rail-steering are;

Turn tight circles around buoys and moored boats. Rail the kayak as far as you dare, wetting your spraydeck a little more each time. You will find that the boat is quite stable on its rail if you relax.

Borrow a DRR without a rudder, it’s fun and its superb skill practice.

Do a regular training sessions without your rudder: Pick a calm, windless day. Lift your rudder out of the water and keep it there using Duct-tape. It will be frustrating at first and you’ll need to use a lot of sweep strokes until you get used to anticipating the kayak turning. Then you’ll be more able to rail-steer it earlier and more effectively. This also a useful skill to learn for the inevitable, sometime in the future when your rudder cable breaks!

Do railing drills where you lift one rail as high as you dare, and paddle for 20 strokes or more until your core muscles start to ache. Either paddle in circles or use the rudder to keep straight. This drill has multiple benefits of strengthening your core, enhancing your proprioception (balancing skills) and it enhances your confidence in your stability by kinaesthetically demonstrating the “edge of stability” of your kayak.

Summary for multisport kayak river racing:

Knowing how to use the rail (edge) of your kayak is the most fundamental multisport kayak skill;

Life-saving if you’re caught on a strainer hazard.

As a beginner it’s the difference between staying upright and capsizing. “Fart at the fast water”

For advanced racing, rail-steering is faster and can be the difference between 1st and 2nd place.

Turning your kayak costs valuable energy that could be better used for forward propulsion.

Rudders are the least efficient to turn, but are a necessary evil, use the rudder tactfully and sparingly

First, plan your route well in advance to minimise turning, and to maximise use of hydraulic features of the river, (such as fast current).

When a change of direction is required, rail-steer, then sweep stroke and lastly the rudder to fine tune.

With experience you will learn to rail-steer more and rudder-steer less

With practice you’ll learn to anticipate early when to use a sweep stroke to help a turn

As you become more confident in moving water, you will be able to judge from closely observing the incoming fast water from one side or the other how aggressively you’ll need to fart at the fast water and whether a low brace support stroke is needed or not, or whether railing is enough and you can keep powering forward with full power.

You’ll develop strong core muscles and good proprioception by using your rail often.

Typical Waimakariri Rapids

A brief history of the NZ phenomenon of multisport kayaking.

The first multisport athletes in the early 1980’s used basic white-water kayaks such as the Tiger, Olymp etc. Then much faster, imported Down River Racer (DRR) kayaks emerged such as the Delphin and Vision series in the mid 80’s. DRR’s do not have rudders, they steer only by the kayaker planning ahead, rail-steering (bilge-steering), sweep strokes and utilising the features of the river to turn their kayak. In the mid to late 80’s Grahame Sisson departed from ICF regulations, pioneering longer, sleeker kayaks with rudders. Kayak design evolved rapidly to suit NZ rivers with multiple kayak designs and manufacturers.

I recall long and exciting discussions about fast hull designs. I was the freshly graduated engineering theorist, bubbling with what I thought were clever ideas, that were never conceived in the entire history of boat design. Grahame Sisson patiently listened and then calmly explained that he’d already tried these ideas and hundreds of others too. Gyro, has an intelligence and experience in hull design that we often mistake as eccentricity. Put simply, for a kayak hull to be fast, it must slip through the water with as little disruption to the water as possible because disruption costs energy. (Without getting carried away in Hydrodynamic-speak, kayak hull design for maximum speed is reasonably complex as one needs to optimise factors such as resistance due to skin friction, eddy making and wave making which end up compromised by the practical requirements of metacentric height, manoeuvrability, comfort and transportability.) Hulls are narrow and sleek so as to promote smooth flow as the water flows from bow to stern with nil or little flow separation. A rudder disrupting this smooth flow presents massive drag.

It has always been a challenge for beginner multisport athletes to get competent in kayaking and even more of a challenge to learn the skills to master rivers and white water. When compared with running and biking which most people learn to do as children, kayaking is typically a relatively unfamiliar sport. Ever since the beginning of multisport in the 80’s, there has been robust debate over the best way to teach, manage, and regulate the “grade 2 kayaking certificate” as a pre-requisite for entering multisport races with moving water. In addition, beginner kayakers usually have a difficult decision when purchasing their first kayak to get the right balance between stability and speed.

Steve Gurney Brief intro.

Steve started kayaking in the University of Canterbury Canoe Club in 1982 with white water, slalom and canoe polo. In the 1980’s Multisport racing began in NZ where Steve began river racing in DRR’s such as the Delphin and Vision. He has many kayak river race wins under his belt, but to summarise those he’s most proud of, he won the Cameron Descent in Malaysia (2-day, class 4 white water) paddling a Wavehopper DRR, and was the South Island DRR champion in1986. As a sponsored athlete he worked with Sisson kayaks assisting Graham as he pioneered the design of specific multisport Kayaks for the NZ multisport phenomenon. He won 9 Coast to Coast races, of course using the Sisson Evolution kayak with which he assisted in the design. Steve has a Mechanical Engineering degree and aims to apply that knowledge to improve sports equipment design.

Steve offers coaching for those who are serious about improving their racing results. Email steve@stevegurney.co.nz to advance your racing.

Comments